Allergy testing

IMPORTANT The information provided is of a general nature and should not be used as a substitute for professional advice. If you think you may suffer from an allergic or other disease that requires attention, you should discuss it with your family doctor. The content of the information articles and all illustrations on this website remains the intellectual property of Dr Raymond Mullins and cannot be reproduced without written permission.

Summary

Identifying avoidable allergens is an important part of allergy management. Your doctor will normally ask you a series of questions in order to identify avoidable environmental triggers. This will often be followed by allergy testing using skin prick tests or RAST or Immunocap. Allergy testing helps your doctor to confirm your sensitivity so that appropriate avoidance advice can be given. Results of skin allergy tests are available within 15 20 minutes. It is important to note that all test results must be interpreted in the context of a careful history.

Skin prick testing

Preparations for skin testing

Medications with antihistamine-like actions (antihistamines, some cold remedies, tricyclic antidepressants) are normally withheld for 3-5 days before testing as these will interfere with the results of testing. You may also be advised to avoid creams and moisturisers on your forearms for a similar period of time to reduce the likelihood that allergen extracts will "run" into each other.

How testing is done

Skin prick testing is most commonly performed on the forearm, although the back is sometimes used. The arm is first cleaned with alcohol, then a drop of commercially-produced allergen extract is placed onto a marked area of skin. Using a sterile lancet, a small prick through the drop is made. This allows a small amount of allergen to enter the skin. If you are allergic, a small mosquito-like lump will appear at the site of testing over 15-20 minutes. Skin tests are slightly uncomfortable, but is usually well tolerated and accurate, even in small children and infants.

Last reviewed 29 May 2020

Skin prick testing is normally done on the arm or back using small skin prick lancets (far right). It is normally well-tolerated, even by small children.

Rationale for skin prick testing

Underneath the lining of the skin, gut, lungs, nose and eyes are mast cells. These are designed to kill worms and parasites and contain granules filled with irritant chemicals (including histamine). Mast cells are also armed with proteins called IgE antibodies, which act as remote sensors in the local environment. A person allergic to house dust mite, for example, will have IgE antibodies capable of recognising the shape of dust mite allergens, in much the same way that a lock "recognises" the shape of a key. When this happens, mast cells are triggered to release their contents into the tissues, triggering an allergic reaction.

Selecting the allergens

In patients with hay fever or asthma, testing usually includes house dust mite, cat and dog dander (perhaps other animals if contact occurs), mold spores and relevant grass pollens, weed and tree pollens and sometimes occupational allergens in those with hay fever or asthma. Testing can also be used to confirm suspected food allergy and stinging insect venom allergy. Skin testing has been shown to improve the accuracy of diagnosis in clinical studies.

While food allergy is more common in people with asthma than the general population, it is a rarely triggers asthma alone. Instead, food allergy is usually accompanied by severe itchy hives, swelling or dizziness or gut cramps.

Since irrelevant small false positive reactions to food occur in up to 5 per cent of subjects, and as such results are often misleading, testing for food sensitivity is not considered routine in the absence of a history suggesting food allergy as well.ie. if the clinical problem is hay fever or asthma, one should test for inhaled allergic triggers like dust mite, mold, pollen or pets but not food. If the problem is food allergy alone, it is reasonable to test for relevant food triggers.

Skin testing is not a reliable way of confirming suspected reactions to aspirin or food additives, and you will need to discuss such concerns with your doctor.

Reasons for testing

Skin testing should be performed in all patients suspected of suffering from severe episodic or persistent asthma, as well as in those with suspected hay fever, or suspected allergic reactions to stinging venomous insects or food allergy. There are no age limitations for skin testing, although the very young and the elderly may have diminished skin test reactions compared to other subjects, and the very young (< 2 years) are only occasionally sensitised to inhaled allergens. Since pregnant subjects may experience uterine (womb) contractions if they suffer a severe allergic reaction to testing, testing is usually only be performed in this group if the immediate benefit of testing is considered to outweigh the risk.

Advantages of skin testing

Skin prick testing is the most convenient and least expensive method of allergy testing and results are available within 20 minutes. This allows you to discuss the results with your doctor at the time of testing.

Side-effects and risks of skin testing

Skin tests are slightly uncomfortable, but usually well tolerated, even by small children. Local itch and swelling normally subsides within 1-2 hours. More prolonged or severe swelling may be treated with an oral antihistamine, topical corticosteroid cream and an ice pack. Occasional patients will experience feel dizzy or light-headed and need to lie down. Severe allergic reactions from allergy testing in asthma are very rare.

Older testing methods (“scratch testing”)

Alternative methods such as scratch testing have generally been abandoned because of poor reproducibility, and greater patient discomfort.

Intradermal testing

Intradermal skin testing is sometimes used. A small amount of very dilute allergen is injected into the upper layers of the skin, normally using a diabetic insulin syringe. It is a more uncomfortable test than skin prick testing. While it is more sensitive, is more likely to lead to false positive and clinically irrelevant results. For this reason, it is usually only used for evaluation of patients with sensitivity to antibiotics, anaesthetic drugs or insect venom.

Measuring total IgE

Levels of a protein antibody called total IgE antibody can be estimated from a blood sample.This is often (but not always) raised in people with allergies and in those with internal parasites. It is often very high in people with eczema an a condition known as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Nevertheless, an elevated IgE does not prove that symptoms are due to allergy, and a normal IgE level does not exclude allergy. Thus measuring IgE levels has a limited role to play in assessing patients with possible allergic conditions. Personally, I almost never measure it, as it does not prove symptoms are due to allergy, and there is no relationship between the level of IgE and symptom severity.

Blood allergy testing

The amount of IgE directed against specific allergens can be measured with a blood test. In general, it is less likely to accurately detect allergies than the skin test, and may give misleadingly falsely positive or false negative results. Australian Medicare rebates are also only available for a total of 4 individual allergens or allergen mixes. For this reason, testing is often performed when skin testing is not easily available, when skin condition such as severe eczema or dermographism prevent accurate testing, or when the patient is taking medications (such as antihistamines or tricyclic antidepressants) that interfere with accurate testing. While the term RAST is sometimes still used (implying using a radioactive isotope in the laboratory to do the test), these days more modern methods are used.

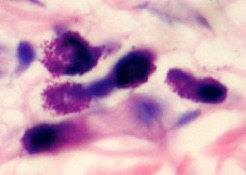

Eosinophil counts

Eosinophils are specialised white cells that are designed to kill worms and parasites. They also can cause inflammation in the tissues in allergy. High levels are sometimes seen in blood samples from people with hay fever, asthma and atopic eczema, as well as in a number of less common conditions. Nevertheless, an elevated eosinophil count does not prove that symptoms are due to allergy, and a normal eosinophil count does not exclude allergy. Thus measuring eosinophil counts has a limited role to play in assessing patients with possible allergic conditions.

Patch testing for contact dermatitis

Patch testing is useful for the assessment of contact allergic dermatitis, such as that triggered by nickel metal, cosmetic preservatives or various plants. Using hypoallergenic tape, commercial standardised allergen paste is applied to a rash free area of skin, most commonly the back. The tapes are normally left in place for 48 hours, being kept dry the entire time. The test site is then "read" at various time intervals, looking for evidence of an eczema-like rash that might indicate sensitivity to a particular allergen.

Patch test allergens (left) and patch tests applied to the back (centre) and results (right).

Challenge testing (provocation)

To establish a diagnosis where there is doubt as to the cause of a severe allergic reaction, challenge testing may sometimes be required. This will normally only be performed using foods or medication under the supervision of a specialist in allergy and clinical immunology with appropriate resuscitation facilities available.

Unproven diagnostic tests

Mainstream allergy diagnosis and treatment is based on a sound scientific knowledge of the components of the immune system and how they work together to sometimes trigger allergies. Conventional allergy testing involves well validated diagnostic methods and proven methods of treatment. By contrast, a number of unproven tests have been proposed for evaluating allergic patients including cytotoxic food testing, Alcat tests, kinesiology, Vega testing, electrodermal testing, pulse testing, reflexology and hair analysis. There is little or no scientific rationale for these methods. Results are not been reproducible when subject to rigorous testing and do not correlate with clinical evidence of allergy. As results may lead to misleading advice or treatments, their use is not advised. No rebate is available under the Australian Medicare system for these tests. These tests are discussed in articles and Position Statements on the Australasian Society for Clinical Immunology and Allergy website (LINK) and on the web site Quackwatch

References

Bernstein, I. L. and W. W. Storms (1995). "Practice parameters for allergy diagnostic testing. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma.The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 75(6 Pt 2): 543-625.

Carter, E. R., E. Pulos, et al. (2000). "Allergy history does not predict skin test reactivity in asthmatic children." J Asthma 37(8): 685-90.

Carter, M. C., M. S. Perzanowski, et al. (2001). "Home intervention in the treatment of asthma among inner-city children." J Allergy Clin Immunol 108(5): 732-7.

Corder, W. T. and N. W. Wilson (1995). "Comparison of three methods of using the DermaPIK with the standard prick method for epicutaneous skin testing." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 75(5): 434-8.

Devenney, I. and K. Falth-Magnusson (2000). "Skin prick tests may give generalized allergic reactions in infants." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 85(6 Pt 1): 457-60.

Grieco, M. H. (1982). "Controversial practices in allergy." Jama 247(22): 3106-11.

Grootendorst, D. C., S. E. Dahlen, et al. (2001). "Benefits of high altitude allergen avoidance in atopic adolescents with moderate to severe asthma, over and above treatment with high dose inhaled steroids." Clin Exp Allergy 31(3): 400-8.

Katelaris, C. H., R. P. Widmer, et al. (1996). "Prevalence of latex allergy in a dental school." Med J Aust 164(12): 711-4.

Lin, M. S., E. Tanner, et al. (1993). "Nonfatal systemic allergic reactions induced by skin testing and immunotherapy." Ann Allergy 71(6): 557-62.

Lockey, R. F., P. C. Turkeltaub, et al. (1989). "The Hymenoptera venom study. II: Skin test results and safety of venom skin testing." J Allergy Clin Immunol 84(6 Pt 1): 967-74.

Maestrelli, P., L. Zanolla, et al. (2001). "Low domestic exposure to house dust mite allergens (Der p 1) is associated with a reduced non-specificbronchial hyper-responsiveness in mite-sensitized asthmatic subjects under optimal drug treatment." Clin Exp Allergy 31(5): 715-21.

Ownby, D. R. and J. A. Anderson (1982). "An improved prick skin-test procedure for young children." J Allergy Clin Immunol 69(6): 533-5.

Ponsonby, A. L., P. Gatenby, et al. (2002). "Which clinical subgroups within the spectrum of child asthma are attributable to atopy?" Chest 121(1): 135-42.

Turkeltaub, P. C. and P. J. Gergen (1989). "The risk of adverse reactions from percutaneous prick-puncture allergen skin testing, venipuncture, and body measurements: data from the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1976-80 (NHANES II)." J Allergy Clin Immunol 84(6 Pt 1): 886-90.

Van Asperen, P. P., A. S. Kemp, et al. (1984). "Skin test reactivity and clinical allergen sensitivity in infancy." J Allergy Clin Immunol 73(3): 381-6.

Van Asperen, P. P., A. S. Kemp, et al. (1990). "Atopy in infancy predicts the severity of bronchial hyperresponsiveness in later childhood." J Allergy Clin Immunol 85(4): 790-5.

Woods, R. K., F. Thien, et al. (2002). "Prevalence of food allergies in young adults and their relationship to asthma, nasal allergies, and eczema." Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 88(2): 183-9.